Topics §

Readings §

- [@2019BOGART-BornThatWay]

- What is the authors’ central idea? What is the new contribution to science of this set of studies?

- Central idea

- Congenital disabilities are often stigmatized as being helpless and dependent

- Acquired disabilities are viewed as being capable of living a “normal” life before their disability

- Different types of stigma for individuals with disabilities, including their self-perception, social relationships, and access to resources and support

- Contribution

- Congenital disability was more stigmatized than the acquired version of the same disability (Studies 1–2)

- People with congenital disability were more essentialized, but less blamed than people with acquired disability (Study 2)

- Manipulating onset and essentialism revealed that when disability was acquired, low essentialism predicted greater stigma through blame (Study 3)

- What is essentialism? What are attribution theories? How is each relevant to understanding disability stigma?

- Essentialism

- Essentialism is the belief that there is an inherent and immutable nature to certain categories, including disabilities.

- It suggests that individuals with disabilities are fundamentally different from those without disabilities and that these differences are fixed and unchangeable.

- Essentialism can lead to stigmatization and discrimination towards people with disabilities.

- Attributions

- Attribution theories, on the other hand, refer to the ways in which people make judgments about the causes of events or behaviors.

- These theories seek to explain why people behave in certain ways and attribute these behaviors to different causes, such as internal factors like personality traits or external factors like situational circumstances.

- Attribution theories are relevant to understanding disability stigma because they can shape the ways in which people view and treat individuals with disabilities.

- Relevance

- For example, people may attribute a congenital disability to internal factors, such as genetics, and therefore view the individual as being fundamentally different from others.

- In contrast, they may attribute an acquired disability to external factors, such as a traumatic accident, and view the individual as being responsible for their disability, leading to blame and stigma. These attributional processes can have a significant impact on the experiences of individuals with disabilities and can shape the ways in which they are treated by society.

- How did the authors test their hypotheses and research questions? How did the three studies differ from one another?

- Study 1

- Study 1 involved an online survey that was completed by 360 participants, who were asked to rate their level of agreement with statements that were designed to measure beliefs about people with congenital versus acquired disabilities.

- The results showed that participants were more likely to view individuals with congenital disabilities as helpless and dependent, while those with acquired disabilities were viewed as more responsible for their condition.

- Study 2

- Study 2 involved a laboratory experiment in which 73 participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with statements that attributed responsibility for a hypothetical disability to either genetic or lifestyle factors.

- The results showed that participants were more likely to attribute responsibility for a disability to lifestyle factors when it was described as acquired, compared to when it was described as congenital.

- Study 3

- Study 3 involved a second laboratory experiment with 148 participants, who were asked to read a hypothetical scenario about a person with either a congenital or acquired disability and rate their level of agreement with statements that were designed to measure stigma.

- The results showed that participants stigmatized individuals with congenital disabilities more than those with acquired disabilities.

- What variables were manipulated in Study 3, and how did the authors manipulate them?

- Manipulation target

- The authors manipulated two variables: the type of disability (congenital vs. acquired) and the age of onset of the disability (early childhood vs. adulthood).

- Method

- Created two different hypothetical scenarios in which the disability was either congenital or acquired. In the congenital condition, the individual had a disability from birth, while in the acquired condition, the individual developed the disability later in life.

- To manipulate the age of onset of the disability, the authors included information about the age at which the disability began in each of the scenarios. In the early childhood condition, the disability began before the age of five, while in the adulthood condition, the disability began after the age of 18.

- Experiment

- Participants in Study 3 were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions: congenital/early childhood, congenital/adulthood, acquired/early childhood, or acquired/adulthood. After reading the scenario, participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with statements that were designed to measure stigma towards the individual with the disability.

- What did the studies find? What conclusions do the authors draw about their findings?

- Individual studies

- First, they argue that the belief that individuals with congenital disabilities are helpless and dependent is a form of essentialism that reinforces the stereotype of disability as a tragedy.

- Second, they suggest that the tendency to attribute responsibility for acquired disabilities to lifestyle factors is a form of victim-blaming that reinforces the stereotype of disability as a personal failure.

- Finally, they argue that the stigmatization of individuals with congenital disabilities can have negative consequences for their self-esteem, social relationships, and access to resources and support. The authors call for a more inclusive and accepting society that recognizes the abilities and contributions of people with disabilities, regardless of the nature of their disability.

- [@2016CRAIG-StigmaBasedSolidarityUnderstanding]

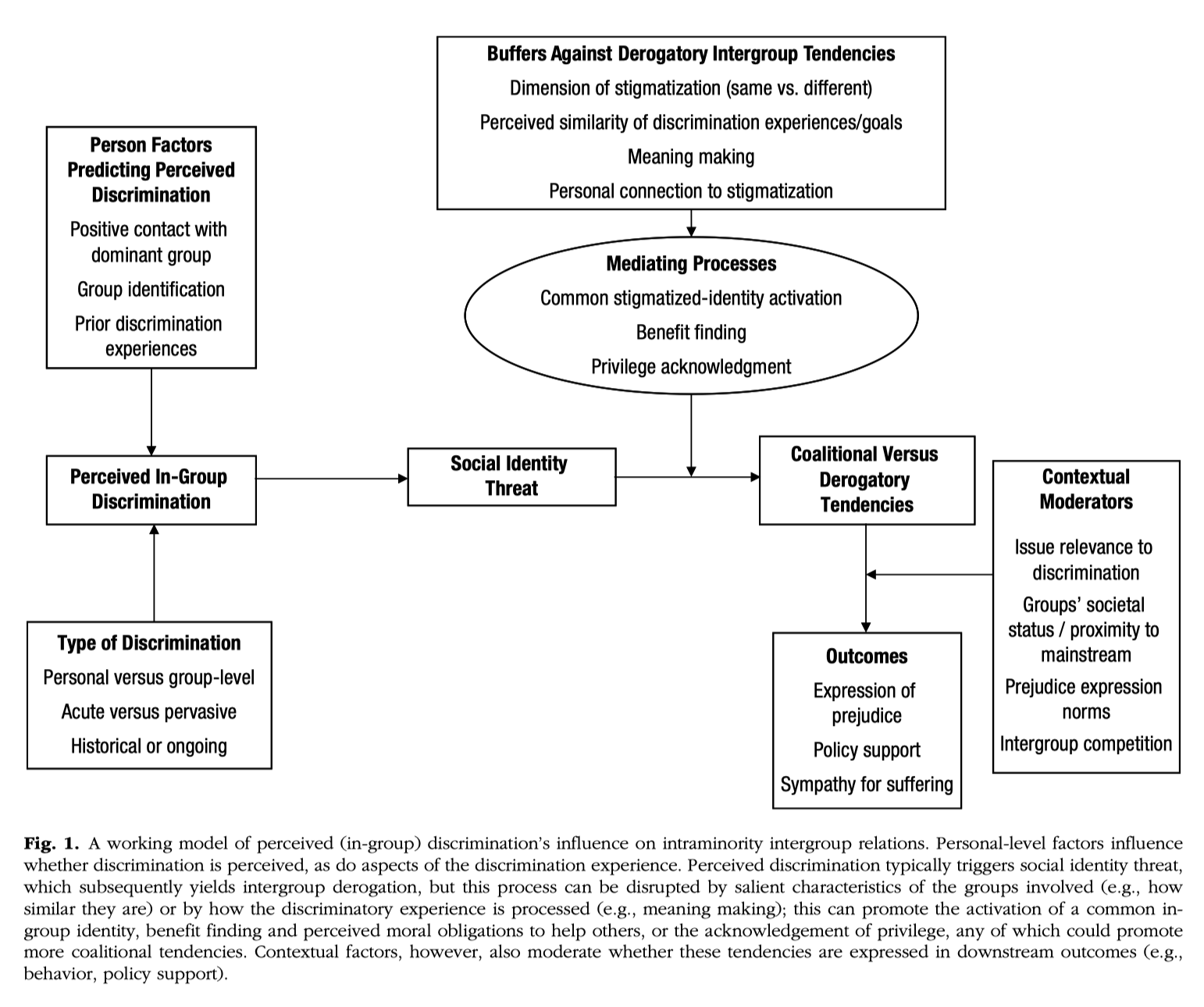

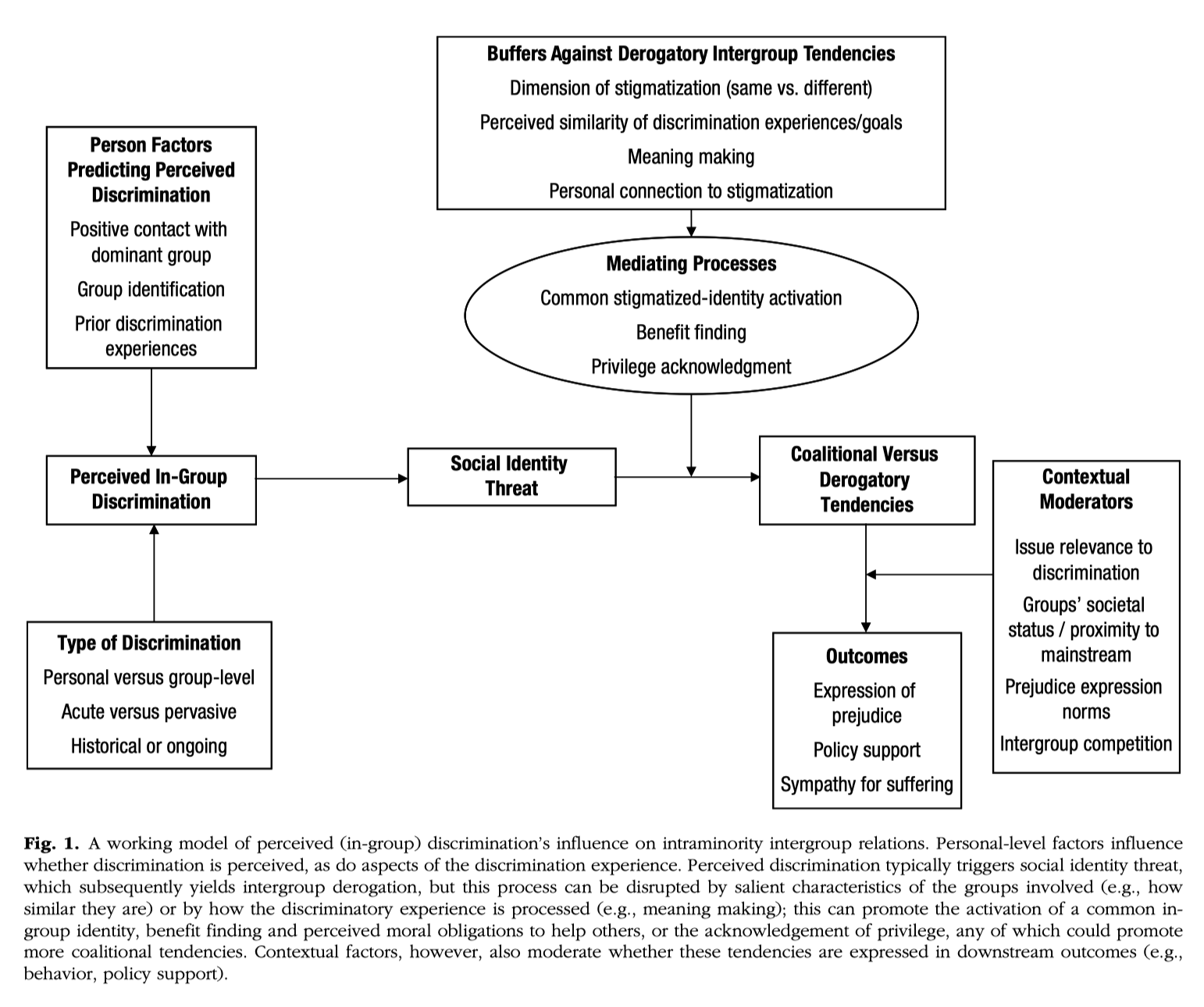

-

- According to the authors, under what conditions would people be more likely to show coalitional, rather than derogatory, attitudes toward other stigmatized people?

- Perceived commonality:

- When individuals perceive that they share similar stigmatized identities with members of other stigmatized groups, they are more likely to show coalitional attitudes toward them.

- The greater the perceived similarity or overlap between stigmatized groups, the more likely individuals are to view members of other groups as potential allies rather than competitors.

- Perceived threat:

- When individuals perceive a common threat from an external source, such as discrimination or prejudice from the dominant group, they are more likely to show coalitional attitudes toward other stigmatized groups.

- In such situations, individuals may perceive that they share a common enemy and may be more willing to work together to fight against this common threat.

- Perceived legitimacy:

- When individuals perceive that members of other stigmatized groups face similar levels of prejudice and discrimination as they do, they are more likely to show coalitional attitudes toward them.

- In other words, if individuals view members of other stigmatized groups as legitimately stigmatized, they may be more likely to empathize with them and view them as allies.

- In contrast, individuals are more likely to show derogatory attitudes toward members of other stigmatized groups when they perceive these groups as different from their own, when they perceive them as less legitimate, or when they view them as competitors for limited resources.

- What are three ways to facilitate more coalitional attitudes among people of different stigmatized groups?

- Explicitly connecting the in-group to another stigmatized group

- Encouraging members of different stigmatized groups to interact with each other can help promote coalitional attitudes by breaking down barriers and promoting a sense of shared identity

- Common experiences or challenges are also associated with more coalitional attitudes among stigmatized groups

- Emphasizing the shared experiences and commonalities between stigmatized groups can help promote coalitional attitudes by highlighting the similarities rather than the differences between groups.

- Meaning making

- Encouraging members of stigmatized groups to work together to achieve shared goals can help promote coalitional attitudes by fostering a sense of collective efficacy.

- Personal connection to stigmatization

Reflecting on one’s personal connection to discrimination may facilitate sympathy with groups stigmatized across dimensions of identity.

- What variables do the authors argue will moderate these effects (i.e., “caveats”)?

- Zeo-sum perceptions (inter-group competition)

- Perceptions of contexts as zero-sum or otherwise competitive may shape the emergence of coalitions

- Perceiving that a similarly low-status out-group is increasing in status or resources tends to evoke more negative attitudes toward the “progressing” group

- Intraminority coalitions are more likely if both groups can attain better outcomes together (i.e., they have common goals), compared to if only one group can attain a valued goal

- Positive contact with the dominant group (Issue relevance to discrimination)

- Positive contact with members of the dominant group or the presumed perpetrating group reduces solidarity among stigmatized groups.

- Prejudice-expression norms

- Perceptions that members of powerful, dominant groups expect the expression of prejudice can lead stigmatized-group members to publicly (but not privately) express prejudice toward a member of another stigmatized group

- Position of groups in society (proximity to mainstream)

- Stigmatized groups’ relative status in society can also shape intraminority intergroup relations. Minority group members often express greater bias against groups perceived to be closer to the mainstream

- ★ [@2022FROST-SocialChangeRelationship]

- What is minority stress? What does prior literature suggest about how it affects sexual minority individuals?

- Minority stress

- Minority stress: the chronic stressors that individuals from marginalized or stigmatized groups experience as a result of their minority status.

- In the context of sexual minority individuals, minority stress refers to the stressors that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer individuals face as a result of their sexual orientation.

- Effects on sexual minority

- Prior literature has suggested that minority stress can have negative consequences for the mental and physical health of sexual minority individuals.

- This stress can arise from experiences of discrimination, victimization, and rejection from others, as well as from internalized homophobia, or negative attitudes and beliefs that individuals may internalize about their own sexual orientation.

- Minority stress model ^3cc37f

- The minority stress model proposed by Meyer (2003) posits that minority stress can lead to a range of negative outcomes for sexual minority individuals, including increased risk of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicide.

- Minority stress can also impact the quality of sexual minority individuals’ relationships, as it can lead to decreased intimacy, relationship satisfaction, and commitment

- What is the social change hypothesis?

- Social change hypothesis

- Changing social and legal attitudes toward sexual minorities may lead to improvements in the quality of same-sex relationships

- The hypothesis suggests that as society becomes more accepting of sexual minorities and provides legal protections for same-sex couples, sexual minorities may experience fewer stressors related to their minority status and may be better able to form and maintain high-quality relationships

- Contrast with minority stress model

- The social change hypothesis contrasts with the minority stress model, which suggests that even in the face of changing social and legal attitudes, sexual minorities may continue to experience stressors related to their minority status that impact their relationships.

- This paper aims to investigate the extent to which the social change hypothesis holds true, and to explore whether minority stress still plays a significant role in the quality of same-sex relationships in the current social and legal climate.

- What is the main idea that this study was testing? What is the logic for this idea?

- Main idea

- The main idea that this study was testing is whether the social change hypothesis, which suggests that changes in societal attitudes and legal protections for sexual minorities may improve the quality of same-sex relationships, holds true in the current social and legal climate.

- Logic

- The logic behind this idea is that as society becomes more accepting of sexual minorities and provides legal protections for same-sex couples, sexual minorities may experience fewer stressors related to their minority status, which in turn may lead to better relationship quality.

- What methods did the authors use to study this idea?

- Ideas

- Test this idea by examining the relationship between social change variables (such as societal acceptance of sexual minorities, legal recognition of same-sex relationships, and public support for same-sex marriage) and relationship quality variables (such as intimacy, relationship satisfaction, and commitment) among a sample of same-sex couples. The study also aimed to explore the extent to which minority stress variables (such as experiences of discrimination and internalized homophobia) still play a role in the quality of same-sex relationships, even in the context of changing social and legal attitudes toward sexual minorities.

- Method

- The authors used a cross-sectional survey design. They recruited a sample of 822 individuals who were currently in a same-sex relationship and had been in that relationship for at least six months

- Participants completed an online survey that assessed a range of variables related to social change (such as societal acceptance of sexual minorities, legal recognition of same-sex relationships, and public support for same-sex marriage) and relationship quality (such as intimacy, relationship satisfaction, and commitment). Participants also completed measures of minority stress, such as experiences of discrimination and internalized homophobia.

- The authors used regression analyses to examine the relationships between social change variables and relationship quality variables, and to explore the extent to which minority stress variables mediated or moderated these relationships. They also conducted exploratory analyses to examine potential differences in these relationships based on factors such as gender, race/ethnicity, and age.

- What did the study find? How strong do you find the evidence to be for their hypotheses?

- Result

- The study found partial support for the social change hypothesis, which suggests that changes in societal attitudes and legal protections for sexual minorities may improve the quality of same-sex relationships. Specifically, the study found that societal acceptance of sexual minorities and legal recognition of same-sex relationships were positively associated with intimacy, relationship satisfaction, and commitment among same-sex couples. Public support for same-sex marriage was positively associated with intimacy and commitment, but not with relationship satisfaction

- However, the study also found that minority stress variables, such as experiences of discrimination and internalized homophobia, were negatively associated with relationship quality among same-sex couples, and partially mediated the relationship between social change variables and relationship quality

- The evidence for the hypotheses was moderately strong, as the study used a large sample size and statistical analyses to examine the relationships between variables. However, the study was cross-sectional, which means that it cannot establish causal relationships between variables. Additionally, the study relied on self-report measures, which may be subject to biases and limitations. Future research that uses longitudinal or experimental designs may provide stronger evidence for the social change hypothesis and its relationship with same-sex relationship quality.

Lectures §